1.19 Give Him the Chair!

If I had stuck Dad's feet into a bucket of cement and thrown him into Puget Sound, you would have been the tiny little splash that followed him!

The chair, the chair, the most famous chair, I suppose, in television history (perhaps the Mastermind chair ranks up there — if you know of a more famous chair, please let me know in the comments). Sat right in the middle of Frasier’s living room, Martin’s chair is at the centre, quite literally, of every episode, almost a character in itself, the immovable presence of his father inserted into his otherwise impeccable bachelor lifestyle. But Give Him the Chair is the first of a couple of episodes where the chair is the subject of the episode, where its significance is laid bare, where the dynamics it symbolises are made explicit.

In this episode, Frasier decides to get rid of the hated chair, “a runny split-pea green and mud-brown striped recliner with the occasional spot of stuffing popping out from underneath a strip of duct tape”, and buy his father a new chair. Niles helps him justify it as an act of support, allowing Martin to move past his use of the chair as a transitional object, a comfort blanket, between his old life and new. Together they visit a furniture store, which gives the brothers an opportunity to indulge the pleasure of distaste. Frasier, more so even than Niles, is the quintessential bourgeois; taste is how he distinguishes himself from the everyday person. He prides himself on it. Surrounded by others willing to surround themselves with recliners and La-Z-boys, he can recognise his own elevation from the masses. It’s ironic, but not really, that his models for good furniture are all arch-modernist architects, whose initial attempts to produce for the masses have become, in their own way, exclusive signifiers for good taste.

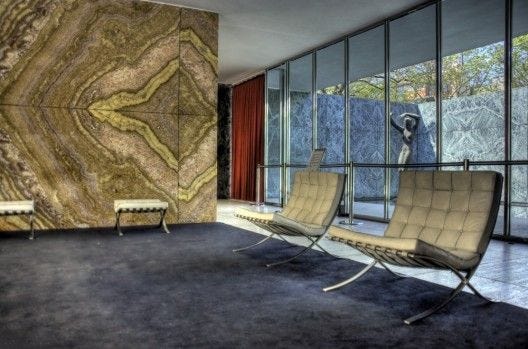

The Barcelona Chair in situ in Mies van der Rohe’s German Pavilion

Frasier tells the store clerk he’s looking for something between a Mies van der Rohe and a Le Corbusier. Both were designed by their architect namesakes for the interiors of exhibition spaces built for large scale international expositions. Van der Rohe’s chair, the Barcelona Chair, was designed for the German Pavilion at the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, in collaboration with the German designer Lilly Reich. Its sleek, low profile (actually a 75cm cube) echoes the aristocratic chairs of ancient Rome, and were the only features (aside from a single sculpture) in this groundbreaking modernist construction. The building was intended to symbolise the ideals of Weimar Germany, being democratic, open and progressive: quite different to Frasier’s ideal of the chair as something explicitly out of the cultural and financial reach of the working person.

Le Corbusier and Perriand’s LC2 Grand Confort

Le Corbusier’s furniture was also designed as a collaboration of a female designer whose role has been pushed into the background in favour of the male genius architect. In this case, it was with Charlotte Perriand, a designer who pioneered a set of tubular framed furniture that manifested Le Corbusier’s belief that a chair was “a machine for sitting in”, echoing his architectural maxim that a house was “a machine for living in”. These chairs echoed the sleek focus on function that characterised early modernist design, with the foundation principle that form follows function: that is, that if a designed object works well, it will look good. The chair Frasier is likely referring to is one of Perriand’s masterpiece, the LC2 Grand Confort, a take on a classic “club” armchair, which was also debuted in 1929, this time in the Salon d'Automne, an exhibition of art and decorative arts in Paris.

Coco Chanel’s sofa in her apartment in the Paris Ritz

Frasier clearly regards himself as a connoisseur. In a later episode a shot of his bathroom reveals another Le Corbusier and Perriand collaboration, the LC4, and his sofa, he is proud to boast, is a replica of one designed by (fellow fascist sympathiser, like Le Corbusier) Coco Chanel. Meanwhile, the chair Martin’s Barcalounger replaces in the pilot episode of the show is another icon of modernist design, Marcel Breuer’s 1925 Bauhaus creation the Wassily Chair, whose pioneering seamless steel tubing design was to influence Le Corbusier and Perriand.

The Fake Chanel, the Wassily, the Eames and the Wassily, all in the pilot show.

If you watch any popular culture from the past 70 years at all, you’ll likely recognise many of these chairs, even without knowing their designers. Their profiles have become a visual byword for an out-of-touch anti-democratic elitism that the designers themselves claimed to want to overturn, yet, due to their fame and the uncanny persistence of capitalist consumerism, they have come to symbolise. Their presence on film and TV sets is a visual trigger for the viewer, in the same way that the sculptures of Alexander Calder are supposed to register any setting as home to pretentious, probably meaningless modern art. It is precisely because of their iconic, democratic design that they are so recognisable.

Frasier relaxing in his Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman

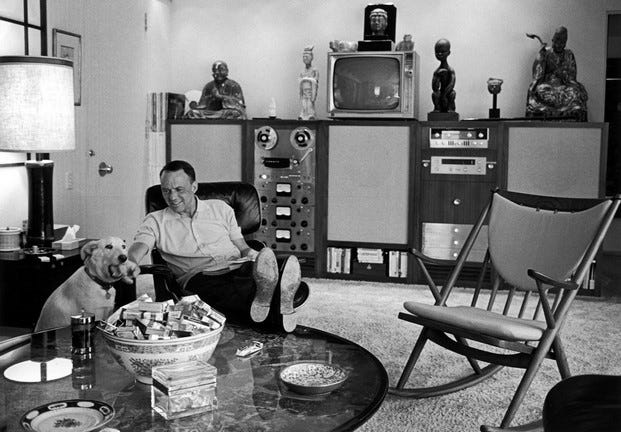

Neither the Grand Confort nor the Barcelona, however, are as recognisable as the chair that Frasier himself actually owns, a chair that performs the same pop culture function but is recognisably American, within the legacy of American commercial modernism, Greyhound bus, Philip Johnson, Coca-Cola and all. That’s the 1959 Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman, designed by the married architects, industrial designers and experimental filmmakers Charles and Ray Eames. Like the modernist designers earlier in the twentieth century, the Eames wanted to produce furniture for the masses, but their work, using cheaper industrial materials like plywood and zippers, had a decidedly West Coast, All-American vibe. Charles Eames described the chair as having the look of “a well-used first baseman's mitt”. Only 4 years after its design, it made its first appearance on screen, in the 1963 Jane Fonda movie Sunday in New York. It somehow fits that of all the modernist designs, this is the one Frasier owns; it manages to marry both the bourgeois values and an everyman quality that is central to the tension of the show. Of all of the chairs, it’s the only one you could imagine Martin sitting in, even if he couldn’t himself. After all, it was a chair owned by his hero, the epitome of American masculine and democratic post-war culture, Frank Sinatra.

Ol’ Blue Eyes relaxing in his Eames, with his dog, his reel-to-reel player, his collection of Buddhas, and about 300 packets of cigarettes

But Martin won’t give up his recliner, commonly known by its generic trademark, the La-z-boy (actually, his model is made by the brand Barcalounger). The la-z-boy was actually pioneered in the late twenties, at exactly the same time as the modernist icons, but its class signifier is entirely different. Mass produced, cheap, and popular, it’s everything Frasier’s favoured chairs claimed to aspire to, but instead it signifies tastelessness, comfort, and actual function over form. But it’s not simply because he thinks it’s ugly that Frasier resents it. It’s because it is sentimental; it’s the chair in which Martin watched the Moon Landings, the chair in which he learnt he was a grandfather, the chair in which his wife would wake him to take him to bed. It’s symbolic of memories of a point in his life in which Martin felt himself to be a real man, in a real man’s America.

The chair is Martin, the stone in the shoe, the impediment to self-realisation, the reminder of everything that Frasier wants to escape from, the class position, the crude, sporty masculinity, the Americanness, the Dad. The persistence of the chair in his domestic space is an assault on his sense of self. That’s what it means to Frasier. But, as I mentioned in 1.1 The Good Son, the chair functions within the show as symbolic of grief itself, the “unspeakable and unmentionable gargoyle that parks itself in the centre of your life. Its hideous presence interrupts everything, a growth on the libidinal energy of forward motion.” As the first season begins to draw itself to an end, the significance of the episode is that this is how things will remain. Frasier will not free himself of his father, the life they are building together will not free themselves of grief, and the impeccable bourgeois decor will not free itself of the recliner chair.

Check out more of my writing at utopian drivel.